Heirs traced to Brazil: The case of Ernst Polaczek

by Romy Langeheine and Cora Chall

After a search over several years, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar has traced the rightful heirs of a “Rätselalphabet” designed by Adele Schopenhauer, and restituted the prints.

>> read German translation here

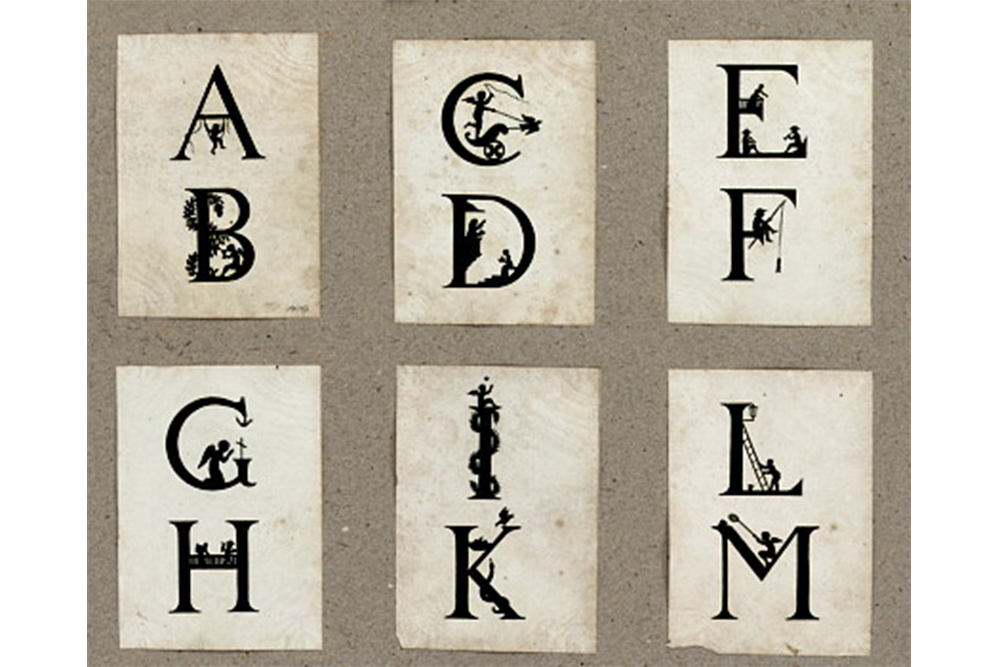

In 1820, Becker’s paperback compendium “for convivial entertainment” reprinted a “Rätselalphabet” (“puzzle alphabet”, “riddle alphabet”) in 13 images, based on silhouettes by Adele Schopenhauer (1797–1849). The sister of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer was a writer but also excelled in the skill of making paper silhouettes. Her mother Johanna Schopenhauer maintained a literary salon in Weimar, where Johann Wolfgang von Goethe used to be a regular guest. It was probably this connection between Goethe and the Schopenhauer family which prompted the purchase of prints of the “Rätselalphabet” by the Goethe National Museum in March 1936. The acquisition ledger of the museum lists the date of the purchase and the price of 40 Reichsmark, but also the seller’s name: Prof. Dr. Ernst Polaczek.

Since 2010, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar has been undertaking a systematic review of its holdings, thus in chronological order and comprehensively, to identify cultural property seized as a result of National Socialist persecution. Since the year of the acquisition in 1936 gave rise to suspecting a purchase of such seized items, the circumstances of the silhouette alphabet’s acquisition went under scrutiny. The main question was: who was Prof. Dr. Ernst Polaczek?

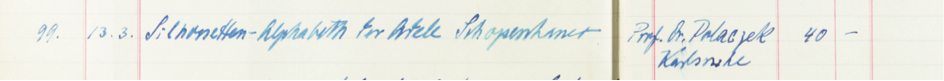

The entry on the acquisition ledger of the Goethe National Museum confirms the purchase of the »Silhouetten-Alphabet der Adele Schopenhauer«, and lists as seller Prof. Dr. Polaczek as well as a purchase price of 40 Reichsmark. The place of residence noted as »Karlsruhe« proved to be erroneous in the course of the investigation. At that time Ernst Polaczek was resident in Freiburg im Breisgau. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

The “Rätselalphabet” was created by Adele Schopenhauer, the sister of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Ernst Polaczek was born in 1870 in Reichenberg (today Liberec/Czech Republic) and studied art history in Strasbourg from 1893. He embarked on an academic career: following his doctorate, he remained as assistant professor at the University of Strasbourg where he habilitated in 1899. Eight years later, Ernst Polaczek also took on the management of the local museum for applied arts, the Städtisches Kunstgewerbemuseum of Strasbourg. On the eve of World War I, he was appointed honorary professor at the University of Strasbourg as well as director of the Strasbourg Museum of Fine Arts. After the end of the war, Ernst Polacek was expelled from what was now again French Alsace, together with all German civil servants. He continued to live with his wife Friederike Polaczek in Munich until he was offered the post of director of the Memorial Hall in Oberlausitz and the associated Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Görlitz in 1928. He was able to work there for five years until he was banned from his profession in 1933 due to the National Socialist anti-Semitic laws: because of his Jewish descent, he was forced into early retirement.

Ernst Polaczek during his tenure as director of the Oberlausitz Memorial Hall in Görlitz, circa 1930. © Görlitzer Sammlungen für Geschichte und Kultur, Kulturhistorisches Museum

Ernst and Friederike Polaczek then moved to Freiburg im Breisgau. It is highly likely that Ernst Polaczek was forced to sell part of his art collection during this period in order to make a living for himself and his wife. His correspondence with the Freiburg finance authorities also shows that he was planning to emigrate from Germany: he pledged securities in order to finance the so-called Reich Flight Tax (“Reichsfluchtsteuer”).

Ernst Polaczek died in Freiburg in January 1939. His widow was the sole heiress of the art collection which included outstanding objects of faience. Various museums urged Friederike Polaczek to sell her collection of valuable ceramics, which she finally agreed to do. Like almost all Jewish citizens living in Baden, Friederike Polaczek was deported to France in October 1940 and subsequently was interned by the French authorities in the Gurs camp. She managed to escape and hide in Grenoble until 1942. Here she was caught during a raid, deported to the extermination camp Auschwitz and murdered there.

The Klassik Stiftung Weimar considers the prints as seized due to Nazi persecution, as it can be assumed that the persecution brought about the sale. In accordance with the Washington Principles agreed by 44 states in 1998, fair and just solutions are to be sought in such cases, together with the legal successors of the former owners.

Ernst and Friederike Polaczek did not have children. Research revealed that two cousins of Friederike Polaczek had been named as heirs, who were able to escape to South America during the Holocaust. After a search of several years, the descendants of these cousins could be traced in Brazil. The Klassik Stiftung Weimar came to an agreement with them to return the prints of the silhouette alphabet. Since February 2021, these have been with their rightful owners in Brazil.

“She only survived three weeks after her deportation”