The case of Arthur Goldschmidt

by Romy Langeheine

The case of Arthur Goldschmidt is one of the biggest restitution cases in the German library system. Provenance researchers in Weimar have reconstructed under which circumstances the passionate collector Arthur Goldschmidt, whose library comprised 40,000 volumes in total, sold parts of it to the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv.

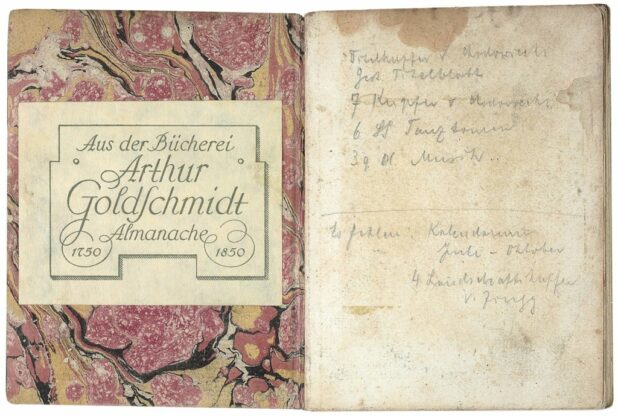

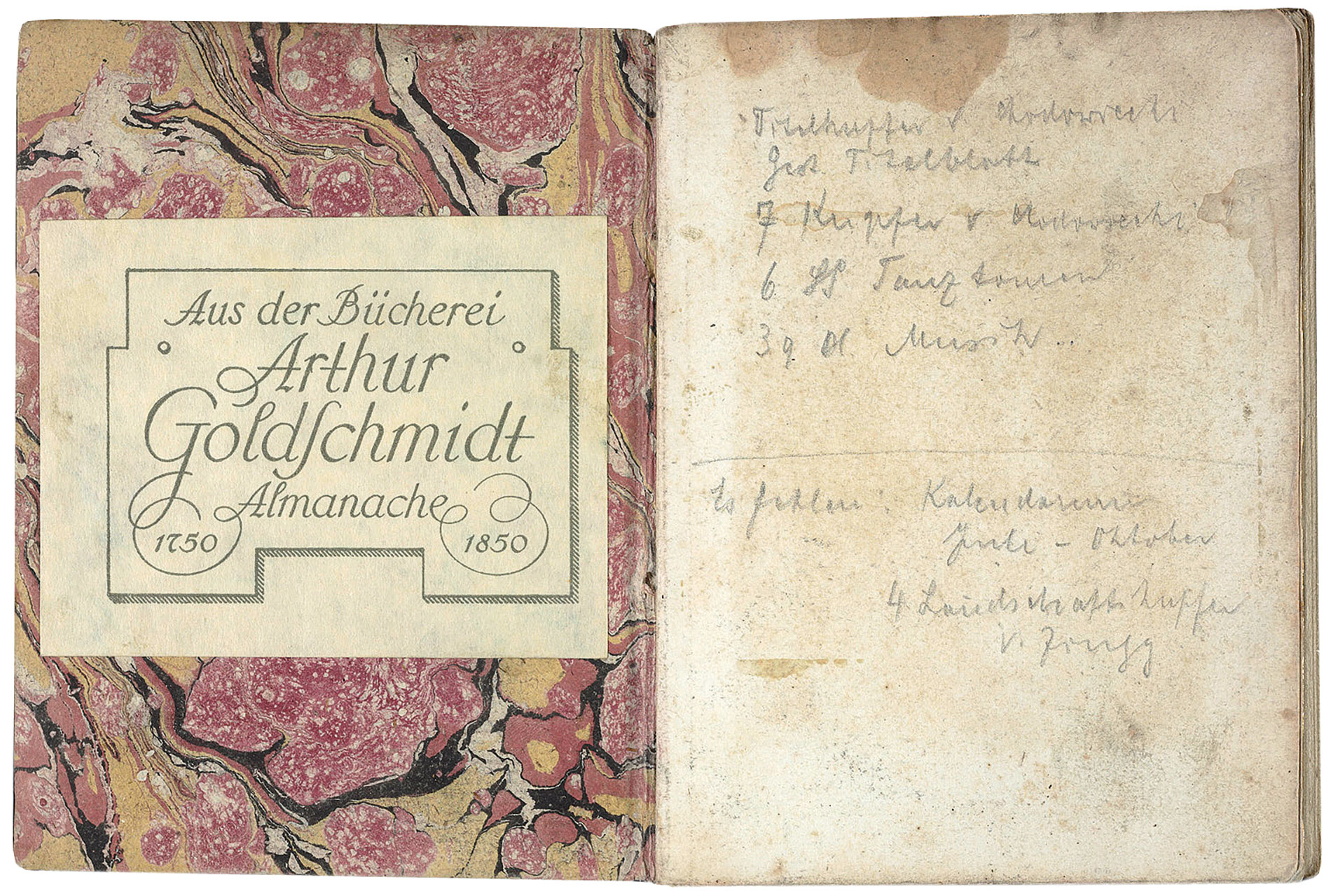

In the course of the investigation in the holdings of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, the researchers found books with the bookplate

“From the Arthur Goldschmidt Library – Almanacs 1750–1850.”

As the pasted note referred to a private former owner, the historians began to reconstruct the history of Arthur Goldschmidt and his books.

Based on the bookplate, the history of Arthur Goldschmidt and his almanac collection could be reconstructed. It turned out that these circa 2,000 volumes had been looted by the Nazis. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Arthur Goldschmidt was born in Leipzig in 1883; his family was of Jewish descent. Like his father before, he became a merchant.

As a passionate book collector, Goldschmidt built up a library consisting of 40,000 volumes over the years, indexed and cared for by a specially employed librarian.

A focus of the collection lay on literary yearbooks, so-called almanacs: approximately 2,000 copies of these rare and partly very valuable works from the 18th and 19th centuries were compiled by Goldschmidt. In 1932, he published a book on “Goethe in the Almanac.”

After his father’s death, Arthur Goldschmidt took over the management of the company – a firm dealing in animal feed. But with the regime of the National Socialists from 1933 on, conditions in the agricultural economy changed:

Newly issued directives fixed prices and strongly restricted trade in agricultural goods.

These measures conduced to the so-called “Gleichschaltung,” the Nazi regime’s enforced system of conformity, also applied to the farming community and designed to oust Jewish business-owners out of the agricultural trade.

Soon, Arthur Goldschmidt’s turnover no longer covered neither expenses nor the living costs of his family.

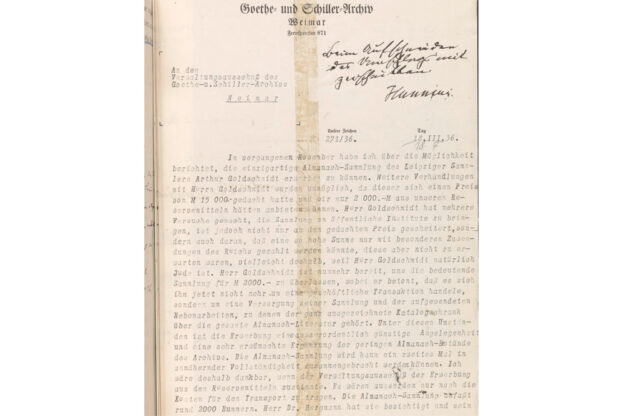

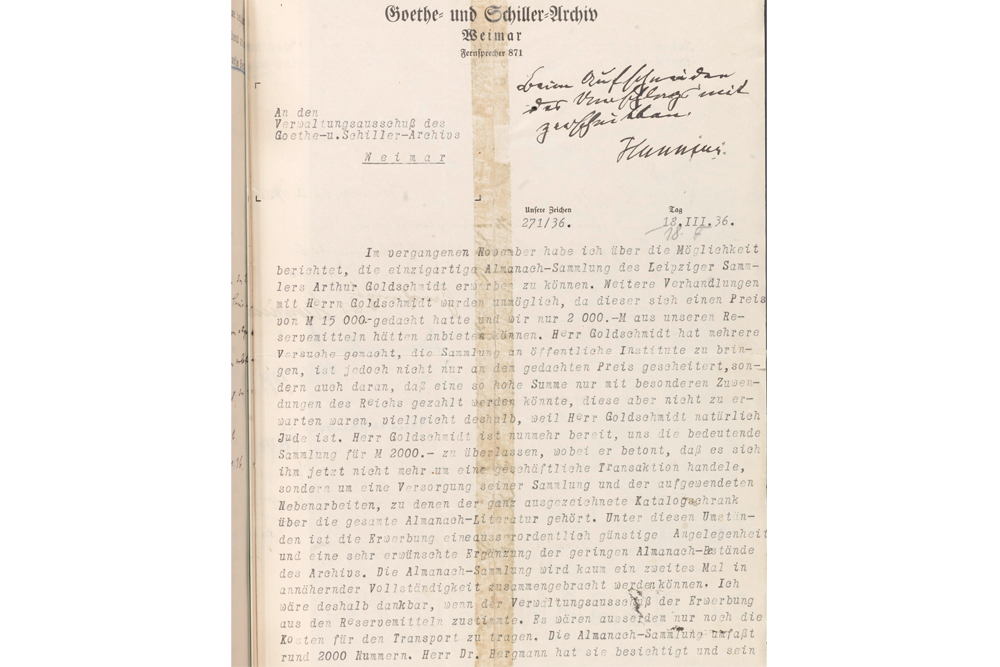

Letter from Hans Wahl, Director of the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, to the administrative committee of the archive regarding the acquisition of the Arthur Goldschmidt collection of almanacs, 18 March 1936. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

In 1935, Goldschmidt was forced to sell his library and offered his collection of almanacs to the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv in Weimar.

Prolonged price negotiations followed. Hans Wahl, archive director at that time, summarized the proceedings in a letter dated 18 March 1936 to the archive’s administrative committee:

“Further negotiations with Mr Goldschmidt became impossible, since he had imagined a price of M 15 000 and we would only have been able to offer 2 000.-M from our reserve fund.

Mr Goldschmidt made several attempts to transfer the collection to public institutions, but these failed, not only because of the asking price but also because of the fact that such a large sum could only be paid with special funding by the Reich, which however is unlikely to materialize, perhaps because Mr Goldschmidt is, of course, Jewish.”

Wahl also outlined how much the archive benefited from this situation:

“Under these circumstances, the acquisition is an exceptional opportunity and a highly desirable addition to the archive’s sparse almanac holdings.”

In 1936, Arthur Goldschmidt finally sold for merely 2,000 Reichsmark. His collection of almanacs as well as the associated card index created by himself went to the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv in Weimar. In December of the same year, he had to close down his company.

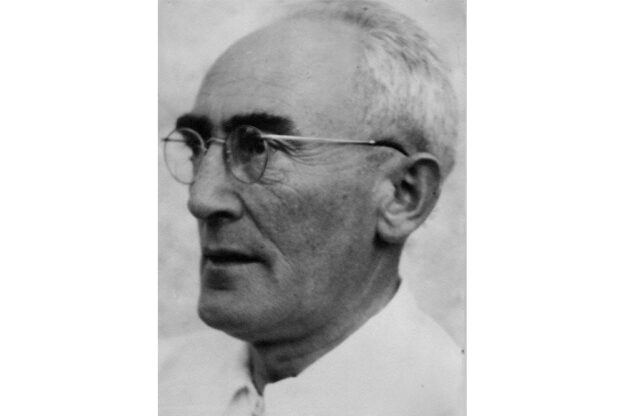

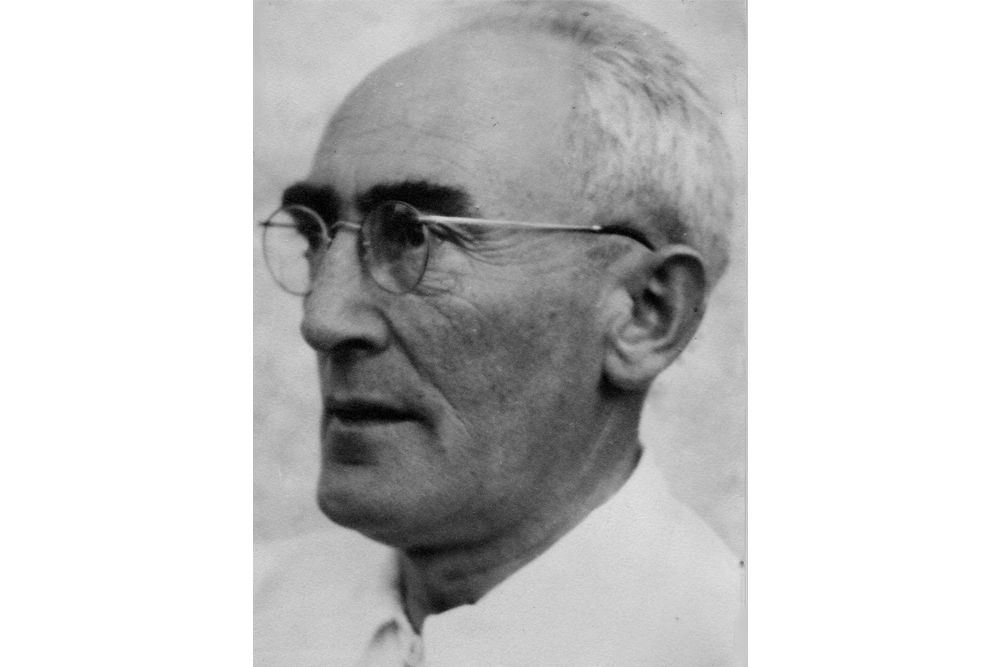

Arthur Goldschmidt, 1950. © Private collection

Goldschmidt tried to regain an economic foothold in Nazi Germany as a wholesale stamp dealer. But his efforts failed.

In November 1939, Arthur Goldschmidt and his wife Henriette fled from Leipzig via Genoa to South America. He died impoverished in Bolivia in 1951.

His collection of almanacs was transferred from the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv to one of the predecessor institutions of the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in 1954/55.

In 2006, the provenance researchers were able to identify heirs of Arthur Goldschmidt. In 2007, the descendants accepted an invitation to Weimar, where they visited the library and the collections.

Two years later, the heirs and the Klassik Stiftung Weimar found a joint solution: the collection was to remain in Weimar.

After the value of the collection had been appraised, the Klassik Stiftung Weimar acquired Goldschmidt’s almanacs and is therefore today their rightful owner.

The Mobile display case presenting the case of Arthur Goldschmidt’s collection of almanacs, seized due to Nazi persecution, will be exhibited until the end of April 2017 in the entrance hall of the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv.

On the series “Nazi loot in the Klassik Stiftung Weimar”

In the collections of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, there is wrongfully acquired cultural property. Since 2010, the foundation systematically investigates so-called Nazi-looted art and aims to find fair and just solutions with those who were victims of persecution or their heirs. In 2011, the foundation included this task in its mission statement.

In several cases, objects identified as Nazi-looted art could be returned to the heirs of the former owners. Since November 2015, the Mobile display case has been on an itinerary through the entrance halls of the different institutions belonging to the Klassik Stiftung Weimar, presenting individual cases of cultural property seized due to Nazi persecution and documenting the history of the former owners.

At each location, which changes every three months, the display case also informs about the history of persecution of the former owners.

In addition, a blog entry is to be published on each case.