The painful history behind a donation

by Marie Florentine Holte

For the first time, the Goethe National Museum will exhibit six drawings by Christoph Heinrich Kniep. The objects are evocative with regard to the artist and travel companion of Goethe, but they also speak of the tragic fate of their former owner.

>> read German translation here

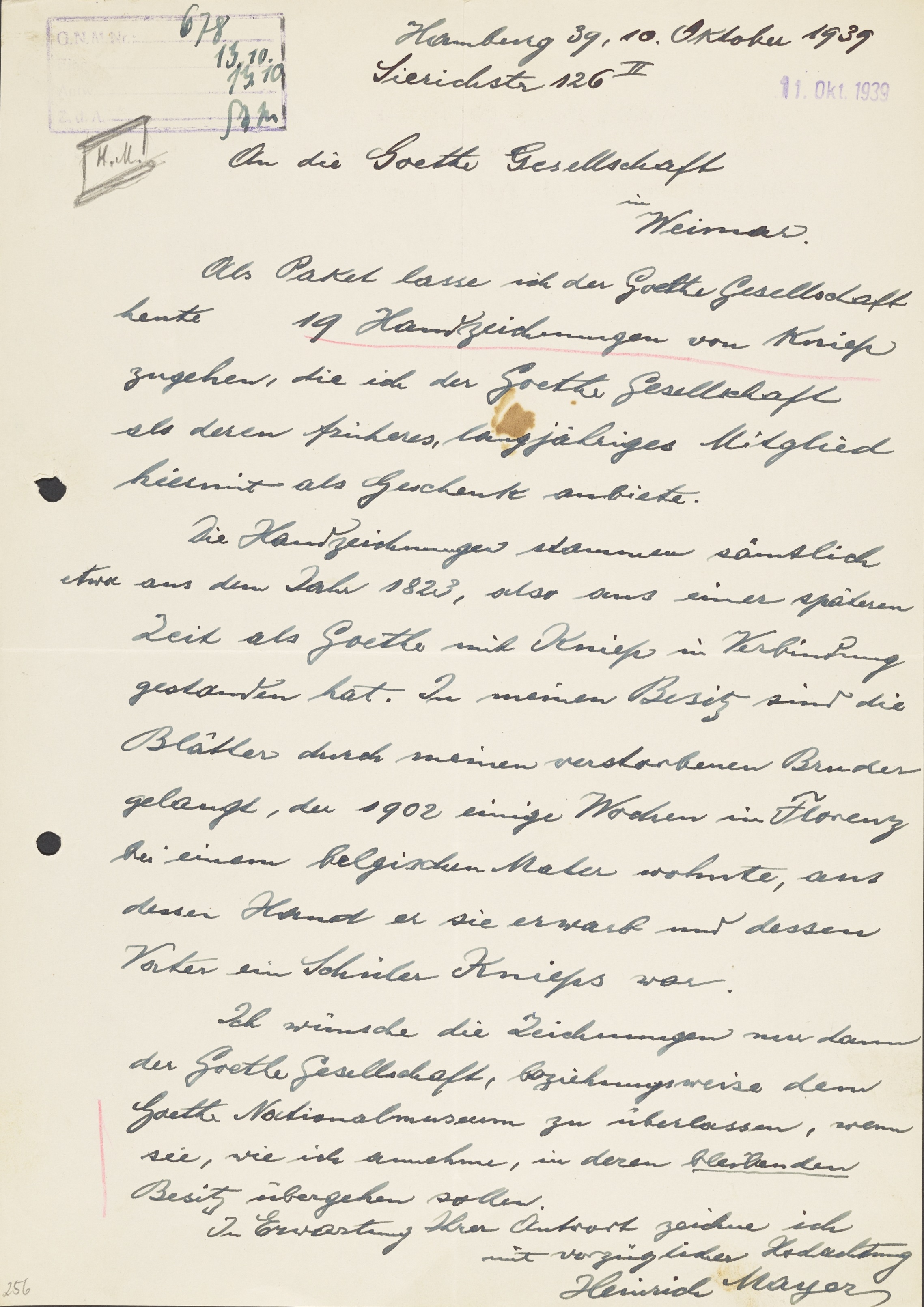

81 years ago, on 13 October 1939, the Goethe Society received a letter from Heinrich Mayer from Hamburg, in which he offered to donate “19 hand drawings by Kniep” to the Goethe National Museum. To Goethe aficionados, Christoph Heinrich Kniep (1755–1825) from Hildesheim was known as Goethe’s drawing teacher and travel companion on a journey to Sicily.

A cabinet exhibition curated by Nora Belmadani and Marie Florentine Holte now presents these small-scale, low-key drawings for the first time on their own, while at the same time honouring their previous owner Heinrich Mayer. The letter of donation at the centre of the display encourages the viewer to see these drawings within the context of the personal history of its former owner.

Deported to a concentration camp in 1942

The provenance researchers of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar investigated the origin of the Kniep group in detail. To begin with, they checked the entry in the running acquisition ledger of the Goethe National Museum: “Donated by Heinrich Mayer in Hamburg, Sierich-Str[asse] 126.” There was no further information. In the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, they found the letter of donation to the Goethe Society in Weimar. Here, Mayer explained that he had inherited the drawings from his brother, who had in turn bought them from the son of a drawing student of Kniep’s in Florence.

Letter from Heinrich Mayer to the Goethe Society, 10 October 1939. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

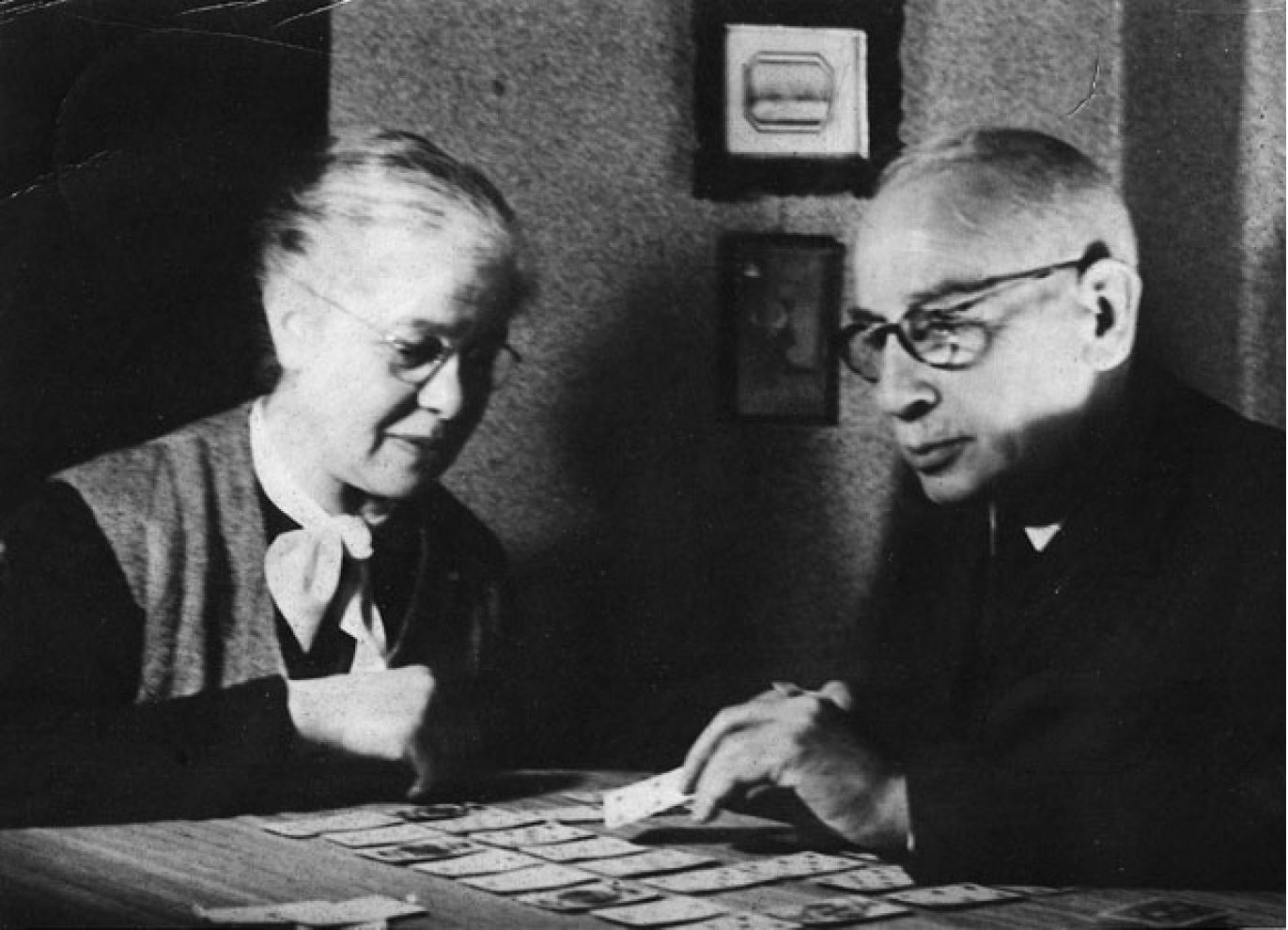

Research on the internet yielded further biographical details: Heinrich Mayer (1866–1942) had been a merchant in Hamburg and the owner of a firm importing coffee. He and his wife were persecuted by the National Socialists due to their Jewish descent. Mayer lost his membership in the Goethe Society as early as 1933. Over the following years, the National Socialists drove him to financial ruin. In 1939, he had no choice but to sell his company.

When Mayer donated the drawings to the Goethe National Museum, he had already lost his entire assets. In 1942, he and his wife were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp where Heinrich Mayer died within the same year. His wife was killed later in the Auschwitz concentration camp.

Marie and Heinrich Mayer in Hamburg, after October 1938. © Die Patriotische Gesellschaft von 1765, Hamburg

“We must assume that Heinrich Mayer feared for his last remaining possessions. These included the group of drawings by Kniep,” explains Sebastian Schlegel, provenance researcher at the Klassik Stiftung Weimar. In the Goethe National Museum, Mayer felt that the sketches would be safe.

For today’s provenance research team the facts soon became clear: the donation had to be regarded in the context of individual persecution and a situation of distress. The Klassik Stiftung Weimar therefore decided to restitute the drawings to the heirs of Heinrich Mayer and reacquire them from the owners. Since 2018, the group of Kniep drawings is rightfully owned by the Goethe National Museum, after almost 80 years.

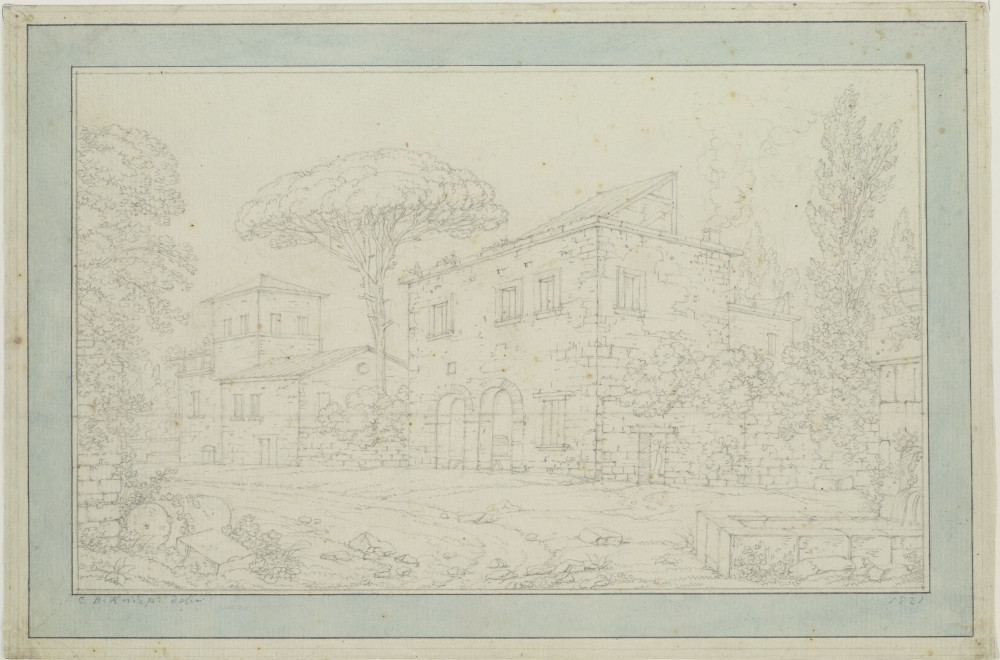

Christoph Heinrich Kniep (1755–1825), Houses in the country (1821), Pencil on paper. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

The drawings now on view were created circa 35 years after Kniep’s journey with Goethe and depict studies of the Italian landscape, executed with great precision. On the pencil drawing “Houses in the country” from 1821, for example, the typical architecture of southern Italian houses is meticulously rendered. The trees can be identified as cypresses and pines. The central perspective is accurate.

Sales to distinguished travellers

“Studies like these, so-called vedute, were made for sale to educated and noble travellers on the Grand Tour,” says Hermann Mildenberger, head of the Graphic Art Collections of the Klassik Stiftung Weimar. The art historian Nora Belmadani adds: “At the same time, the sketches were a kind of reference book, where Kniep could look up motifs.” This artist after all specialized in creating large-scale drawings of idealized Italian landscapes, based on his repertoire of sketches.

Christoph Heinrich Kniep (1755–1825), Heroical landscape with Apollo and Midas (1789), Pen in grey-black over minimal traces of pencil drawing, brown wash, border in grey-black pen, coloured with a brush in grey-green. © Klassik Stiftung Weimar

One example for his work technique is the picture “Heroical landscape with Apollo and Midas” (1789) which Duchess Anna Amalia bought from Kniep during her journey through Italy: elements from various sketches are combined to form a large-scale Arcadian landscape. Pictures like these are presumed to be Kniep’s most impressive creations.

“The sketches formerly owned by Mayer however are not among his prominent works and probably did not circulate much in the art trade, but rather in different private collections,” as Hermann Mildenberger explains. It was a matter of “absolutely specialist interest.”

Mayer’s fate is deeply affecting

As an admirer of Goethe and a member of the Goethe Society in Hamburg, Mayer knew about the collector’s value of the drawings. He wanted to find a safe place for them. And he decided, even in the greatest financial distress, to give them away. “Mayer’s fate is deeply affecting – and it does not take much to empathize with his position: in a situation of utter hopelessness, nevertheless to take a decision based on free will, and to make an impact,” as the provenance researcher Schlegel describes it. For this, we owe him gratitude.